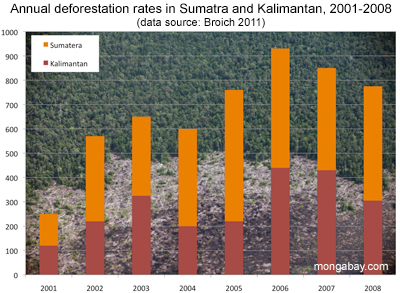

Over the past twenty years Indonesia lost more than 24 million hectares of forest, an area larger than the U.K. Much of the deforestation was driven by logging for overseas markets. According to the World Bank, a substantial proportion of this logging was illegal.

While deforestation rates have dipped since the late 1990s, illegal logging remains a problem in Indonesia. In fact it is seen as one of the biggest challenges for Indonesia in meeting the greenhouse gas reductions targets pledged by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono: in 2009 the Indonesian President pledged to unilaterally cut the country's emissions 26 percent from a projected 2020 baseline.

While deforestation rates have dipped since the late 1990s, illegal logging remains a problem in Indonesia. In fact it is seen as one of the biggest challenges for Indonesia in meeting the greenhouse gas reductions targets pledged by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono: in 2009 the Indonesian President pledged to unilaterally cut the country's emissions 26 percent from a projected 2020 baseline.

Curtailing illegal logging may seem relatively simple: hire more forestry police to conduct more patrols, strengthen fines, prosecute cases, and implement better tracking systems for legitimate timber. But at the root of the problem of illegal logging is something bigger: Indonesia's land policy. The bulk of Indonesia's forest is owned by the state, which historically has doled out large concessions — often tens of thousands of hectares in extent — to logging companies. Local communities mostly lose out, leaving some to seek opportunities from illicit timber harvesting. Without clear ownership rights to land, communities have little incentive to reject illegal logging or manage forests for the long-term. The model — which has contributed to the abandonment of traditional land stewardship in many areas — has driven large-scale devastation of Indonesia's rich forest ecosystems.

Can the tide be turned? There are signs it can. Indonesia is beginning to see a shift back toward traditional models of forest management in some areas. Where it is happening, forests are recovering. For example "people's forests" in Java are, for the first time in generations, regrowing. Given a stake in forest ownership, communities in Java have an interest in reforestation for timber production and other benefits afforded by forests.

Telapak, a membership organization with offices on several Indonesian islands, understands the issue well. It is pushing community logging as the "new" forest management regime in Indonesia. Telapak sees community forest management as a way to combat illegal logging while creating sustainable livelihoods.

Telapak, a membership organization with offices on several Indonesian islands, understands the issue well. It is pushing community logging as the "new" forest management regime in Indonesia. Telapak sees community forest management as a way to combat illegal logging while creating sustainable livelihoods.

Telapak has since expanded its goals to include securing and protecting local community ownership and management rights of forests. The broader scope is inherently more complex than advocacy work. Telapak must now work to build technical capacity on the ground, push legal reform, delve into politics, and build business models that sustain and nurture community forest management. The path promises to be a challenging one, but Telapak is growing: its members now manage more than 200,000 hectares of forest land across Java, Lombok, Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua. It is also working in areas outside the forest sector, including fisheries, the ornamental fish trade, and mass media. All the while, Telapak continues its campaigning efforts, including a recent exposé on illegal logging and palm oil plantation development in Indonesian New Guinea: Papua and West Papua.

Source: Mongabay

No comments:

Post a Comment

Many thanks for your contribution. Where applicable, we will respond to you here.